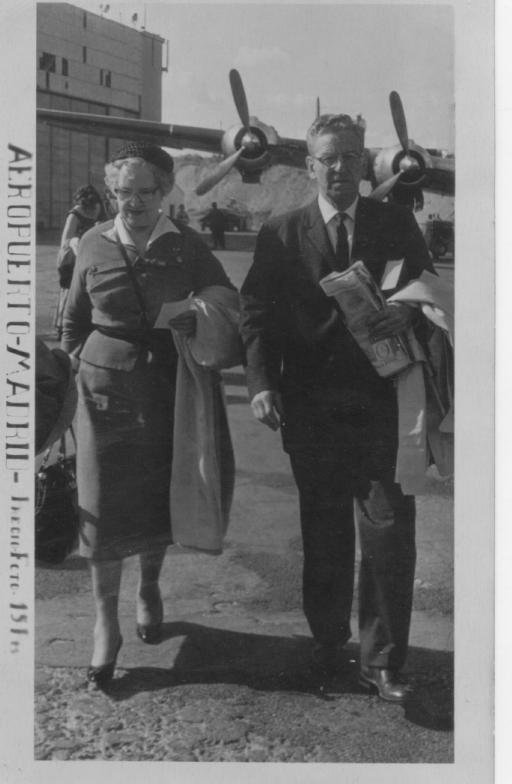

I should know by heart the route from Pittsburgh airport to the South Hills. Snow, not failing memory, interferes with the homing instinct. I’m with Karen, star of my rental car’s global positioning system. After agreeing on the route through Bridgeville, we pass the auto repair shop on Painters Run frequented by my father (1985†). I don’t feel puzzled anymore that Dad warmed to its owner. A doctor and a mechanic have in common holding people’s fates in their hands.

Karen: No, go straight! What’s wrong with you?

By the time we reach the intersection of Gilkeson and Washington/Route 19, Karen doesn’t have to remind me to continue east on Connor. In fact she earns my respect for knowing Gilkeson inexplicably becomes Connor.

Mom is preparing a welcome supper at her apartment on Academy. She knows I am taking a detour to where her parents are buried, St. Anne Cemetery on Hoodridge. She does not know that I am visiting the artist Andy Warhol’s eternal home not far away. Andy (1987†) is easy to find on the east-facing slope of St. John the Baptist Byzantine Catholic Cemetery, which is beside Connor before it ends at Library Road/Route 88. There is a place in the Warhol aesthetic for the irony of unfashionable Bethel Park PA, but I’m with the fans who mourn the site as incommensurable with his renown. The creator of superstars belongs in internationally famous Green-Wood, Père-Lachaise, Highgate or Forest Lawn – or in locally status-conscious Allegheny.

An iris, a nod to the fleur-de-lis trademark of Campbell’s Soup, shares the glory of the scene – or its ordinariness, depending upon one’s perspective – with other grave goods left by previous disciples: Coca-Cola bottles, Brillo boxes, etc. Unwillingly, I picture myself six feet under, in black cashmere suit and paisley tie, wearing platinum wig and sunglasses, and holding prayer book and brittle, grey-red rose – a human time capsule winking at the curious: Open me up! See how well-preserved I am! It must be the soup in my veins, mmm good! I was a naive boy who accepted pop culture at face value. Tomato soup from a factory warmed you up as well as Mom’s. One cola tasted better than all others. Dad should buy the stridently colored box of soap-infused steel wool. The flower won’t last long in this weather.

Renewed flurries add to the already thick accumulation. Inside the car I snap a redundant photo like thousands before me as three millennials arrive with their smartphones. Like homing pigeons, they congregate for selfies in front of Figment, a camera on a nearby pole by the access road – a 24/7 live feed supported by the Andy Warhol Museum.

Karen: Silly boy, I can read your mind like a map. Now that you’ve spotted cameras, one side of you wants to hang out in the Warholian simulacrum, while another wants to stay on the sidelines, imagining the millennials are Edie Sedgewick, Ronald Tavel and Rene Richard in Andy’s film “Kitchen.” And as a good Catholic you don’t wish their screen tests to be failures. You want new generations to be brilliant successes, basking forever in stardom, right?

Karen seems to have forgotten that I am a recovering Catholic. I make a half-hearted Sign of the Cross and trip over the two prayers in my repertoire, Our Father and Hail Mary. Their impact in the hereafter, if any, I ask to be extended to Andy’s parents Andrej (1942†) and Júlia (1972†), who are behind their son. I nearly get out to give Figment a (by my standards) theatrical thumbs-up or the finger, both of which would, who knows, win me some fans and land me on the cover of People magazine.

Karen: Pregnant pause…Next stop: your grandparents. Even if the millennials noticed you, they will forget and delete you soon enough.

Being on Connor again reawakens an uncomfortable memory, which forces me to watch a rerun of a near-death experience that occurred on this very pavement. If local, non-fatal, non-crashes made national headlines, the éminence grisé of the Crash Series himself, alive then, might have been tuned to an evening news report about a white-knuckled teen in the back seat of a daredevil friend’s speeding Oldsmobile. My metaphorical rearview mirror (hindsight) allows me to see the brush with death as my first, small glimmer of the fragility of life. Karen jolts me into the present.

Karen: Watch where you’re going!

We are hydroplaning in the choppy wake of a salt truck and nearly rear-end it.

Karen: I prefer my means of a livelihood to live, if you please! Make a left here onto Library Road/Route 88. Travel north until the next light. Now, be careful; any icy patch could send us off the road. Make a left here at Rockwood. We cross the light-rail tracks slowly to allow you to recollect your cherished roly-poly red trolleys (1987†). A right onto Willow past St. Anne School. The original church, where your parents were married, is gone. It survives in their wedding album. Now a quick left onto St. Anne Street.

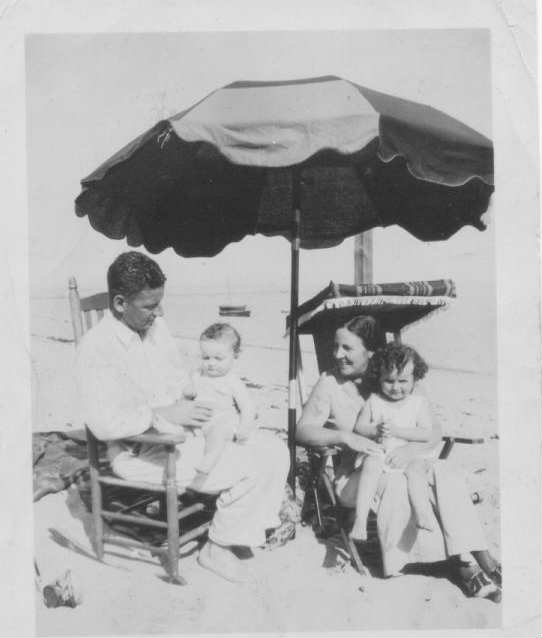

On the cemetery’s access road, I hit the record button of my smartphone’s camera. Frank and Ann (née Kelly) Hennessy (respectively, 1965† and 1971†) rest in peace in the company of my mother’s maternal grandmother, Johanna (née Rochford) Kelly Murphy (1954†).

Grandson: Hello, grandma. Hello, grandpa. I miss you. Here are some forget-me-nots and chrysanthemums. I love you. Thanks for bringing Mom and Aunt into the world. I still see your smile, grandma, and hear you singing at the piano. And thanks for making me oatmeal.

Cut! Thanks for oatmeal?! Perhaps a more suitable memorial is a prepared script. Or a grandparent-cam, in respectful imitation of Figment, complete with mourners (knock on wood). I can hear the public reaction to a grandparent-webcam. Pastor: What would your mother think?! Mother: What would your grandparents think?! Can Mom and the pastor be persuaded, since the family has no moving images or voice recordings, that my grandparents should be permitted to make a photographic impression?

Mom must be juggling final acts of food preparation, so Karen and I race against the clock, or rather crawl in the dangerous road conditions. After descending Hoodridge, we inch along Mt. Lebanon, where I notice a notary, a bar, an office building. They were non-existent to the kid I was. One business was very much present.

Karen: Too bad G.C. Murphy’s closed years ago. I would love some bubble gum or wax bottles or jaw breakers or rock candy.

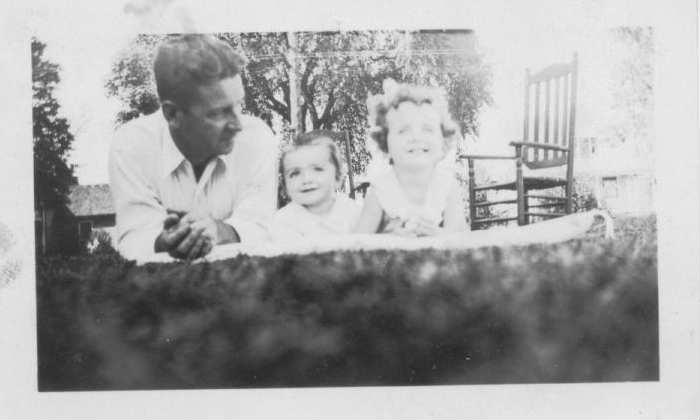

Our lucky streak of navigation continuing (I have one hand on the wheel, the other operating the camera phone), we reach the Sunset Hills neighborhood. At the dead end of Crystal Drive, Grandpa Hennessy, who passed away on my fifth birthday, is shoveling snow. My collection of 35mm slides contains black-and-white photos of him doing the identical thing, and some of him in spring gardening mode. Moving as silently as the scrim of descending flakes, he clears a path along the side of the house. There is no squeak or crunch of rubber boots on powder or of blade scraping against concrete. I follow into the backyard.

Karen: When will you be back?

Grandma Hennessy is in the living-room window, illuminated at her piano, warming the house with Sigmund Romberg (1951†), Victor Herbert (1924†), Cole Porter (1964†), the Gershwins (George 1937† and Ira 1983†), Bing Crosby (1977†) and Pittsburgh’s own Billy Eckstine (1993†) and Perry Como (2001†).

In the same frame, a star-topped white pine whose lights, ornaments and tinsel would find their way to the trees of future generations. In the absence of visual, written or oral evidence, a toy train under the tree on steel tracks ploughs into tunnels of glinting cotton snow, shimmering ribbon and pre-loved wrapping paper. On a lace tablecloth with opaline-bead stitching, Grandma has arranged silverware, frost-mint napkins, crystal tumblers inscribed in a cut-diamond pattern (eggnog for kids, an amber liquid for adults). Outwardly dull pieces of chocolate on bone china cast a spell on my mother and aunt, books in their laps and sugar in their eyes.

The room contains radiophonic voices too. Jack Benny (1974†), for one, never got old, according to my aunt:

Father admired his dry timing. During a meeting at work, somebody slipped in a slide of a nude in a field. Daddy’s response was to turn to the man next to him and ask, “Is that oat or rye?” The man was uncomprehending.

In the street, children who feel no pain pull a toboggan. Bundled up to the point of anonymity, they could be carbon copies of me and my brothers, scurrying toward Country Club and our imitation of Olympic glory on the municipal golf course’s scaled-down version of alpine pinnacles, our feet in three pairs of wool socks in boots with half their clasps undone. They are probably on an instant-chocolate high, playing hyperactive make-believe despite the constraint of puffy snowsuits. I have to rejoin Karen or keep moving in order to avoid freezing to death. In melting slush streaked by car oil and exhaust is a naked and abandoned Ken doll, identical to the Ken dolls of my day and built like them to last an eternity, the absence of genitalia not curtailing a dynasty. Although his hard, plastic skin protects him from the elements, Barbie’s soul mate in his present state resembles a scarecrow more than a metrosexual. I question the manufacturer’s choice of painted, non-reflective, dead eyes.

Ahead, on the transformed golf course, cross-country skiers stick to the high ground, disregarding the course’s “bones,” the variety of natural features which appeal to the makers of golf courses and their cousin, the cemetery builder. Tobogganers have eyes only for the start of their run on the 7th tee. Deer and crow monitor activities of importance to deer and crow. While his offspring wrestle, a father cannot find his wallet, which is lost until spring (or forever) in ice, snow, mud, dead grass and leaves. In windy March too inclement for most golfers, he will be back with a kite and his kids. Their love is worth the price of shoes soaked by the thaw and a damned kite that won’t stay up. Grandpa Hennessy spent untold hours here on his rounds as a World War II air warden and (very) occasional golfer. I can’t remember if he was the sort of man to buy ice cream for us in December. I like to think so. Who is ready for a Skyscraper Cone? It’s never the wrong season for an Isaly’s Skyscraper Cone, held tight as a kite string, as if one’s life depends on it. It’s too late for another detour to enjoy the genuine article at our Isaly’s (1980†) on Washington. Anyway, Mom, minutes away, always stocks ice cream.

Grandfather: That’s it, be yourself.

Grandson: Grandpa?

Grandmother: Your grandfather and I are on a walk, sweetheart.

Grandson: I’m on my way to Mom’s.

Grandmother: That’s nice. Send her our love.

Grandson: When can I interview you for a family history?

Grandfather: Meet us at half past a freckle.

Grandson: I wish I could take a selfie with you.

Grandfather: We wouldn’t be in the picture, but you wouldn’t be alone: The stars are out, day and night.

I point the camera phone toward the last of the Olympians. Thanks to the drop in temperature, their track of white diamonds is faster than it was earlier. Once they are gone, silence will reign for the most part, interrupted occasionally by strollers and canines on evening walks. Stamping my feet and shaking myself, I crack my crystalline shell. In the rental, I block out Old Man Winter by conducting a hypothetical interview set in the family kitchen, with Karen in the all-important role of Mom.

Son: Did you know Andy Warhol’s mother appeared in his 1966 film named after her?

Karen/Mom: I didn’t know he had a mother.

Son: Were you cross-country skiing on the golf course today? I bet I saw your tracks.

Karen/Mom: Don’t sit at the table with your phone.

Son: What’s for dessert?

Karen/Mom: That’s for me to know and you to find out.

Before putting away the phone, I thumb through my newly acquired, raw, unedited source material, including close-ups of pristine snow and its ancient fractures. For future reference I rename the folder of photos, whispering as I type:

streets in undying light.