To copy as in the old days, a reterritorialization of Gustave Flaubert’s Bouvard & Pécuchet (1881) and Harry Newman, Jr.’s Orange Mall (1971), in progress.

Epigraphs

Pictures of an ideal Chavignolles pursued him in his dreams. Flaubert, Bouvard & Pécuchet

We moved from store to store, rejecting not only items in certain departments, not only entire departments but whole stores, mammoth corporations that did not strike our fancy for one reason or another. DeLillo, White Noise (1985)

Product description

Two Orange County Californians meet by chance in Paris. Their chemistry transcends their past experiences of friendship. “Fraternité!” announces Bill, raising a glass of 1970 Château Margaux. Both are screen printers. Both wear Eagles t-shirts. Both have scored the band’s latest album Desperado (Asylum Records, 1973). Phil toasts, “To Ripley’s Believe it or Not!” A Serge Gainsbourg song heard in the Rue de Verneuil tests their compatibility, they flee in a taxi. Tour-guided into the City of Love/Light’s famous Passages, ancestors of America’s suburban shopping centers, the seasoned consumers listen, captivated, to a description of the Passage de l’Opéra, destroyed in World War I. Under one roof were the Théâtre Moderne, Caron (gun smith), Marguerie (music publisher), a philatelist, a cane and walking-stick shop, a hairdresser for ladies, a hairdresser for gentlemen (Courbet paid with a picture), Lemonnier (funeral items made of hair) and a public bath. “Groovy!” (Bill) “Far out!” (Phil). They leave with a “peaceful, easy feeling” (Eagles, Asylum, 1972). At Orly, the travelers use flyers about the haunts of novelists, painters and philosophers as mats to absorb the condensation dripping from their Coca-Colas. On souvenir postcards, under blurbs in six languages, they scrawl caricatures of Citroën Amis. Back in the Golden State, reunited at a scrimmage at Norwalk’s Falcon Field, they hear the autocratic voice of Huntington, retired executive, and follow it to a disquisition on stock markets attended by Costa, Huntington’s factotum, Fullerton, librarian, and Rev. Tustin, football coach. After allotting six days for calm consideration, Bill and Phil shake hands at OC Zoo as partners in conservative investments. Orange Mall tenants are in their portfolio. The shareholders proceed to exasperate franchise owners and store managers by taking a proprietary interest in B. Dalton, La Fiesta, Orange Mall 6, Radio Shack, Russo’s Pets, Sears, Spencer Gifts, Sweats n Surf, Woolworth’s, et al. They see room for improvement.

Copy Characters

Barberou, Bill’s cat

Clemente, tennis player and doctor

Costa, Huntington’s factotum

Dana, waitress

Dumouchel, Phil’s cat

Fullerton, librarian

Huntington, retired executive

Irvine, mayor

Linda, volleyball coach

Margarita, restauranteur

Placentia, real estate agent and Bill’s ex

Stanton, surfer and lawyer

Rev. Tustin, football coach

Vic, Bill’s nephew

Victoria, Bill’s niece

Copy Cameos

Shirley Babashoff, Olympic swimmer

Suzanne Daniels, pupil of Charloma Schwankovsky

Pat Nixon, first lady

Original Characters (partial list)

Barberou, Bouvard’s Paris friend

Vaucorbeil, doctor

Hurel, factotum of Comte de Faverges

Marianne, Madame Bordin’s maid

Dumouchel, Pécuchet’s Paris friend

Gouy, farmer

Comte de Faverges, country gentry

Foureau, mayor and public prosecutor

La Germaine, servant

Beljambe, innkeeper

Madame Bordin, widow of private means

Marescot, lawyer

Abbé Jeufroy

Victorine, protégé of Bouvard and Pécuchet

Victoria, protégé of Bouvard and Pécuchet

Original Cameos

J-B. Fauldes, magistrate

Nicolas Appert, confectioner and inventor

Copy Location

Orange Mall, Orange County, California, USA

Original Location

Chavignolles, Calvados, Normandy, France

Copy

Chapter 1, Paris and Norwalk: friendship, revolution, tourism.

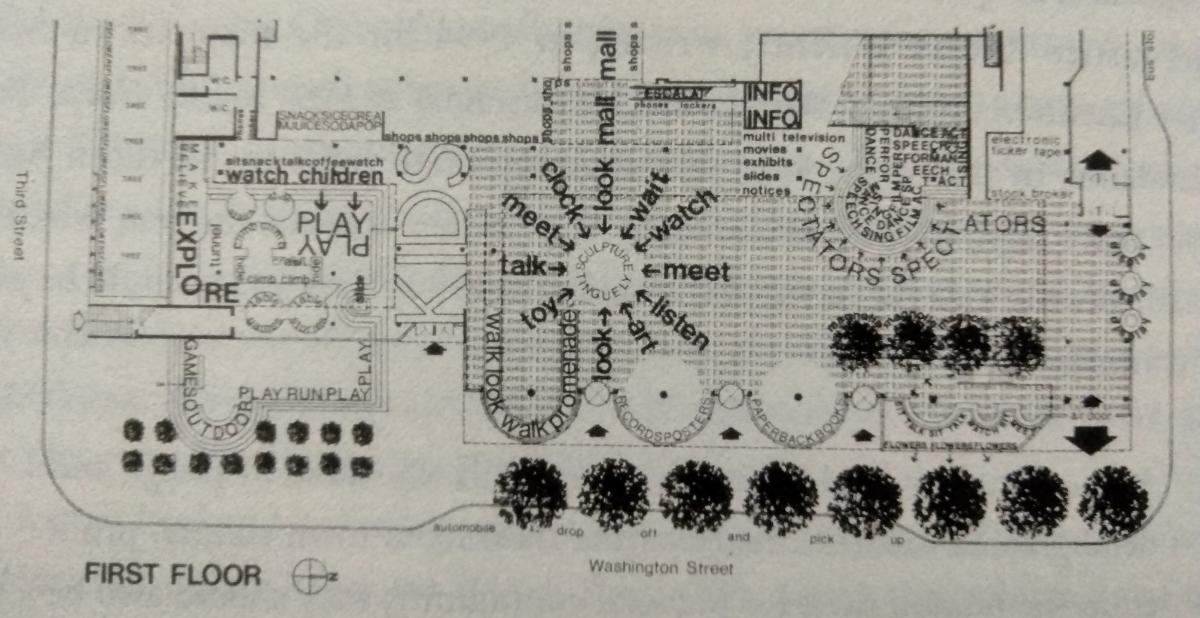

Chapter 2, Orange Mall (Parking Lot and Arcade): investments, overpopulation, aesthetics (graffiti)

Chapter 3, Orange Mall (La Fiesta): veganism, immigration

Chapter 4, Orange Mall (Sweats n Surf): sports

Chapter 5, Orange Mall (B. Dalton): literacy

Chapter 6, Orange Mall (Radio Shack): space ships, weapons

Chapter 7, Orange Mall (Orange Mall 6): movies, tv

Chapter 8, Orange Mall (Sears): politics, poverty

Chapter 9, Orange Mall (Russo’s Pets): futurism

Chapter 10, Orange Mall (Woolworth’s): education, pop music

Chapter 11, Orange Mall (Spencer Gifts): desk for two

Original

Chapter 1, Paris: meeting, friendship, inheritance

Chapter 2, Chavignolles: agriculture, landscape gardening, food preservation

Chapter 3, Chavignolles: chemistry, anatomy, medicine, biology, geology

Chapter 4, Chavignolles: archeology, architecture, history, mnemonics

Chapter 5, Chavignolles: literature, drama, grammar, aesthetics

Chapter 6, Chavignolles: politics

Chapter 7, Chavignolles: love

Chapter 8, Chavignolles: gymnastics, spiritualism, hypnotism, Swedenborgianism, magic, theology, philosophy, suicide, Christmas

Chapter 9, Chavignolles: religion

Chapter 10, Chavignolles: education, music, urban planning

Likely ending, Chavignolles: speeches at the Golden Cross Inn, futurism, narrow escape from prison, desk for two, Dictionary of Received Ideas

A Note on the Text

To copy as in the old days is based on readings of the Alban J. Krailsheimer translation (1976) of Bouvard & Pécuchet, which is “taken from the Garnier-Flammion edition by Jacques Suffel (1966), which incorporates the text established by Alberto Cento for his critical edition of 1964. It [Krailsheimer’s translation] varies in places from earlier editions.”

Bibliography

Louis Aragon, Paris Peasant (Le Paysan de Paris, 1926).

Walter Benjamin, The Arcade Project (Das Passagen-Werk, written between 1927 and 1940, trans. Eiland and McLaughlin, Harvard University Press, 1999). See Notes.

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature (1975) (trans. Dana Polan, 1986). See Notes.

Gustave Flaubert, Bouvard & Pécuchet (1881).

Frank Kafka, Forschungen eines Hundes (Investigations of a Dog, 1922).

Alexandra Lange, Meet Me by the Fountain (2022).

Harry Newman, Jr, Turning 21: A Businessman’s Poetic Odyssey to the New Century (1999).

Matthew Newton, Shopping Mall (2017). See Notes.

Marcel Proust, Remembrance of Things Past (1913-1927), trans. C. K. Scott Moncrieff (1922-1930).

Current Reading

Éric Hazan, The Invention of Paris: a history in footsteps (2002, trans. David Fernbach, 2011).

Éric Hazan, A walk through Paris (2016, trans. David Fernbach, 2018). See Notes.

Future Reading Regina Bittner, The World of Malls (2016). Louis Chevalier, The Assassination of Paris (1977). Ruth Schwartz Cowan, More Work for Mother (1983). Arlene Dávila, El Mall (2016). Michael Galinsky, The Decline of the Mall (2019). Victor Gruen, Shopping Town (2017). M. Jeffrey Hardwick, Mall Maker: Victor Gruen, Architect of an American Dream (2004). Éric Hazan, Paris in turmoil: a city between past and future (2021, trans. David Fernbach, 2022). Alex Wall, Victor Gruen: From Urban Shop to New City (2005). Shay Youngblood, Black Girl in Paris (2000).

Gallery

image credits

Literary Totems: see publishers

Avian Totems: Suzanne Daniels (2023)

Mall Prototype: Eleanor Hohman (1958)

Anchor Store (Dior): Eleanor Hohman (1958)Verbal Plan: The Commons, Columbus IN, Pelli Clarke Pelli Architects

Discography Eagles (1972) Desperado (1973) On the Border (1974) One of These Nights (1975) Hotel California (1976)

Notes

Benjamin

“…the working of quotations into the framework of montage…a determinate literary form, one that has effectively constructed itself (that is, fragmented itself)…” Translators’ Foreward, p. xi

“…Also to be found in the Passage de l’Opéra was the arms manufacturer Caron, the music publisher Marguerie, the pastry chef Rollet, and finally the perfume shop of the Opéra…In addition,…there was Lemonnier…manufacturer of handkerchiefs, reliquaries, and funeral items made of hair.” (Paul d’Ariste, La Vie et le monde du boulevard, 1830-1879 (1930), pp. 14-16) pp. 48-50

“In the Passage Choisel, M. Comte, ‘Physician to the King,’ presents his celebrated troupe of child actors extraordinaires in the interval between two magic shows in which he himself performs.” (J.-L. Croze, Quelques spectacles de Paris pendant l’eté de 1835 (Le Temps, August 22, 1935)), p. 52

Passage du Commerce-Saint-André: a reading room. p. 53

“Once the socialist government had become the legitimate owner of all the houses of Paris, it handed them over to the architects with the order…to establish street-galleries… When all the blocks of houses were thus traversed by galleries occupying…their second story, it remained only to connect these isolated sections to one another in order to constitute a network…embracing the whole city. This was easily done by erecting covered walkways across every street…Walkways of the same sort, but much longer, were likewise put up over the various boulevards, over the squares, and over the bridges that cross the Seine, so that in the end…a person could stroll through the entire city without ever being exposed to the elements…As soon as the Parisians had got a taste of the new galleries, they lost all desire to set foot in the streets of old–which, they often said, were fit only for dogs.” (Tony Moilin, Paris en l’an 2000 (1869), pp. 9-11) p. 53

The gain in time realized for their retail business by the abolition of bargaining may have played a role initially in the calculations of department stores. p. 60

Here fashion has opened the business of dialectical exchange between woman and ware–between carnal pleasure and the corpse. The clerk, death, tall, loutish, measures the century by the yard, serves as mannequin himself to save costs…For fashion was never anything other than a parody of the motley cadaver, provocation of death through the woman, and bitter colloquy with decay whispered between shrill bursts of mechanical laughter. That is fashion. p. 63

An emblem of the power of fashion over the city of Paris: “I have purchased a map of Paris printed on a pocket handkerchief.” (Gutzkow, Briefe aus Paris (1842), S. 82) p. 66

T. Th. Vischer, “Vernünfige Gedanken über die jetzige Mode” (Sensible Thoughts about Current Fashion) in Kritische Gänge (1879). p. 66, et seq.

A little later he [Vischer] speaks of the women thus attired as “naked in their clothes.” T. Th. Vischer, Mode und Cynismus (1861), p. 70.

“The ascendancy of the bourgeoisie works a change in women’s wear. Clothing and hairstyles take on added dimensions…shoulders are enlarged by leg-of-mutton sleeves, and… it was not long before the old hoop-petticoats came back into favor and fulll skirts were the thing. Women, thus accoutered, appeared destined for a sedentary life–family life–since their manner of dress had about it nothing that could ever suggest or seem to further the idea of movement. It was just the opposite with the advent of the Second Empire: family ties grew slack and an ever-increasing the luxury corrupted morals to such an extent that it became difficult to distinguish an honest woman from a courtesan on the basis of clothing alone…Everything that could keep women from remaining seated was encouraged; anything that could impede their walking was avoided. They wore their hair and their clothes as though they were to be viewed in profile. For the profile is the silhouette of someone…who passes, who is about to vanish from our sight. Dress became an image of the rapid movement that carries away the world.” Charles Blanc, “Considérations sur le vêtement des femmes” (Institut de France, October 25, 1872), pp. 12-13. p 74

Louis Aragon devoted 135 pages to this arcade. p. 82. (Passage de l’Opéra)

Plan Tirade. p. 85

Conservative tendency of Parisian life: as late as 1867, an entrepreneur conceived the plan of having 500 Sedan chairs circulate throughout the city. p. 86

Concerning the mythological topography of Paris: the character given it by its gates. Important is their duality: border gates and triumphal arches…On the other hand, the Arc de Triomphe, which today has become a traffic island. Out of the field of experience proper to the threshold evolved the gateway that transforms whoever passes under its arch. pp. 86-7

At the entrance, a mailbox: last opportunity to make some sign to the world one is leaving. p. 87

Apropos of the bicycle: “Actually one should not deceive oneself about the real purpose of the fashionable new mount, which a poet the other day referred to as the horse of the Apocalypse.” L’Illustration, June 12, 1869, cited in Vendredi, Oct 9, 1936. (Louis Chéronnet, “Le Coin des vieux”). p. 97

The Galerie du Thermomètre and the Galerie du Baromètre, in the Passage de l’Opéra. p. 103

“His fatigue had infected the walls of his mansion. The parakeets stood out like his separate thoughts, each one materialized and attached to a pole…”, Rodenberg, Paris bei Sonnenschein und Lampenlicht (Leipzig, 1867), pp. 104-105. p. 105

In the second-to-last chapter of his book Paris: From Its Origins to the Year 3000 (Paris, 1886), Léo Claretie speaks a crystal canopy that would slide over the city in case of rain. “In 1987” is the title of this chapter. p. 109

Man (from Lamartine’s L’Infini dans les cieux (Infinity of the Skies):

“Thinking, with hands that cannot manage the compass,

To sift suns like grains of sand.” p. 118

“Cut off from the will of man, it [the commodity] aligns itself in a mysterious hierarchy, develops or declines exchangeability, and, in accordance with its own peculiar laws, performs as an actor on a phantom stage…Things have gained autonomy, and they take on human features…The commodity has been transformed into an idol that, although the product of human hands, disposes over the human.” Otto Rühle, Karl Marx (1928), pp. 384-5. p. 181

During my second experiment with hashish. Staircase in Charlotte Joël’s studio, I said: “…I can transform the Goethe house into the Covent Garden opera; can read from it the whole of world history. I see, in this space, why I collect colportage images. Can see everything in this room: the sons of Charles III and what you will.” p. 216

Balzac’s interior decorating in the rather ill-fated Les Jardies: “This house…was one of the romances on which M. de Balzac worked hardest during his life, but he was never able to finish it…’On these patient walls,’ as M. Gozlan has said, ‘there were charcoal inscriptions to this effect: “Here a facing in Parisian marble”; “Here a cedar stylobate”; “Here a ceiling painted by Eugène Delacroix”; “Here a fireplace in cipolin marble.”‘” Alfred Nettement, Histoire de la litterature francaise sous le gouvernement del juillet (1859), vol. 2, pp. 266-267. p. 224

The residential character of the rooms in their early factories, though disconcerting and inexpedient, adds this homely touch: that within these spaces one can imagine the factory owners as a quaint figurine in a landscape of machines, dreaming not only of his own but of their future greatness. With the disassociation of the proprietor from the workplace, this characteristic of factory buildings disappears. Capital alienates the employer from his means of production, and the dream of their future greatness is finished. This alienation process culminates in the emergence of the private home. p. 226

Tableau of decadence: “Behold our great cities under a fog of tobacco smoke that envelops them, thoroughly sodden by alcohol, infused with morphine: it is there that humanity comes unhinged. Rest assured that this source breeds more epileptics, idiots, and assassins than poets.” Maurice Barrès, La Folie de Charles Baudelaire (1926), pp. 104-105. p. 250

Poulet-Malassis had his “shop” in the Passage des Princes, called in those days the Passage Mirès. p. 253 [P-M was a friend and publisher of Baudelaire.]

Arcades are houses or passages having no outside–like the dream. p. 406

rite de passage, p. 409

An engraving from around 1830, perhaps a little earlier, shows copyists at work in various ecstatic postures. Caption: “Artistic Inspiration at the Museum.” Cabinet des Estampes. p. 411

“Thirty-six pages for food, four pages for drink…” (Julius Rodenberg, pp. 43-44) Flânerie through the bill of fare. p. 423

“When the first German railway line was about to be constructed in Bavaria, the medical faculty at Erlangen published an expert opinion…: the rapid movement would cause…cerebral disorders (the mere sight of a train rushing by could already do this), and it was therefore necessary, at the least, to build a wooden barrier five feet high on both sides of the track.” Egon Friedell, Kulturgeschichte der Neuzeit (Munich, 1931), vol. 3, p. 91. p. 428

In the musical revue by Barré, Radet, and Desfontaines…performed…on June 9, 1810, Paris in the form of a model…has migrated into the scenery. The chorus declares “how agreeable it is to have all of Paris in one’s drawing room.” The plot revolves around a wager between the architect Durelief and the painter Ferdinand; if the former, in his model of Paris, omits any sort of “embellishment,” then his daughter Victorine straightaway belongs to Ferdinand… p. 429

“The climactic points of the city are its squares: here, from every direction, converge not only numerous streets but all the streams of their history. No sooner have they flowed in than they are contained: the edges of the square serve as quays, so that already the outward form of the square provides information about the history that was played upon it.” Ferdinand Lion, Geschichte biologisch gesehen (1935), pp. 125-126, 128. p. 435

In…Le Voyage de MM. Dunanan père et fils, two provincials are deceived into thinking that Paris is not Paris but Venice, which they had set out to visit…” S. Kracauer, Jacques Offenbach und das Paris seiner Zeit (1937), p. 283. p. 438

…until the entire past is brought into the present in a historical apocatastasis. p. 459 (apocatastasis: restoration of all things.)

“As I study this age which is so close to us and so remote, I compare myself to a surgeon operating with local anesthetic: I work in areas that are numb, dead—yet the patient is alive and can still talk.” Paul Morand, 1900 (1931), pp. 6-7. p. 462

Letter from Wiesengrund of August 5, 1935: “…Dialectical images are constellated between alienated things and incoming and disappearing meaning, are instantiated in the moment of indifference between death and meaning. While things in appearance are awakened to what is newest, death transforms the meanings to what is most ancient.” With regard to these reflections, it should be kept in mind that in the nineteenth century, the number of “hollowed-out” things increases at a rate and on a scale that was previously unknown, for technical progress is continually withdrawing newly introduced objects from circulation. p. 466

To thinking belongs the movement as well as the arrest of thoughts. Where thinking comes to a standstill in a constellation saturated with tensions—there the dialectical image appears. It is the caesura in the movement of thought. p. 475

As rocks of Miocene and Eocene in places bear the imprint of monstrous creatures from those ages, so today arcades dot the metropolitan landscape like caves containing the fossil remains of a vanished monster: the consumer of the pre-imperial era of capitalism, the last dinosaur of Europe. On the walls of these caverns their immemorial flora, the commodity, luxuriates and enters, like cancerous tissue, into the most irregular combinations. A world of secret affinities opens up within: palm tree and feather duster, hair dryer and Venus de Milo, prostheses and letter-writing manuals. The odalisque lies in wait next to the inkwell, and priestesses raise high the vessels into which we drop cigarette butts as incense offerings. These items on display are a rebus: how one ought to read here the birdseed in the fixative-pan, the flower seeds beside the binoculars, the broken screw atop the musical score, and the revolver above the goldfish bowl—is right on the tip of one’s tongue. After all, nothing of the lot appears to be new. The goldfish come perhaps from a pond dried up long ago, the revolver was a corpus delicti, and these scores could hardly have preserved their previous owner from starvation when her last pupils stayed away. And since, to the dreaming collective itself, the decline of an economic era seems like the end of the world, the writer Karl Kraus has looked quite correctly on the arcades, which, from another angle, must have appealed to him as the casting of a dream: “In the Berlin Arcade, there is no grass growing. It looks like the day after the end of the world, and in this condition is put on display. Castan’s Panopticon. Ah, a summery day there, among the wax works, at six o’clock. An orchestrion plays mechanical music to accompany Napoleon III’s bladder-stone operation. Adults can see the syphilitic chancre of a Negro. Positively the very last Aztecs. Oleographs. Street youths, hustlers, with thick hands. Outside is life: a third-rate cabaret. The orchestrion plays, “You’re a Fine Fellow, Emil.” Here God is made by machine.” Karl Kraus, Nachts (1924), pp. 201-202. p. 541

Deleuze and Guattari

Undoubtedly, one can write while eating more easily than one can speak while eating, but writing goes further in transforming words into things capable of competing with food…To speak, and above all to write, is to fast. p. 20

The animal does not speak “like” a man but pulls from the language tonalities lacking in signification; the words themselves are not “like” the animals but in their own way climb about, bark and roam around, being properly linguistic dogs, insects, or mice. p. 22

Kafka does not opt for a reterritorialization through the Czech language. Nor toward a hypercultural usage of German with all sorts of oneiric or symbolic or mythic flights…Nor toward an oral, popular Yiddish. Instead, using the path that Yiddish opens up to him, he takes it in such a way as to convert it into a unique and solitary form of writing. Since Prague German is deterritorialized to several degrees, he will always take it farther, to a greater degree of intensity, but in the direction of a new sobriety, a new and unexpected modification, a pitiless rectification…He will make the German language take flight on a line of escape…To bring language slowly and progressively to the desert. To use syntax in order to cry, to give a syntax to the cry. pp. 25-26

To make use of the polylingualism of one’s own language, to make a minor or intensive use of it, to oppose the oppressed quality of this language to its oppressive quality, to find points of nonculture or underdevelopment, linguistic Third World zones by which a language can escape, an animal enters into things, an assemblage comes into play. pp. 26-27

Already in the animal stories, Kafka was drawing lines of escape; but he didn’t “flee the world.” Rather, it was the world and its representation that he made take flight and that he made follow these lines. pp. 46-7

…what is the ability of a literary machine, an assemblage of enunciation or expression, to form itself into an abstract machine insofar as it is a field of desire? p. 88

Hazan

…[Colonel Rol-Tanquy] prepared the insurrection of 19 August 1944 in the basement of the westerly pavilion. In this building, the Paris highways department now studies road surface materials, the different types of paving and asphalt. p. 28

The builders of today’s hospitals often have marvels close at hand: the architects of the new Saint-Louis hospital had before their eyes every morning the wings dating from Henri IV; those who built the extension of the Cochin hospital could see opposite them the Vale-de-Grâce constructed in the days of Anne of Austria; and here, at Port-Royal, the architects were only a few metres from the buildings of the abbey and monastery. I do not mean that they should have resorted to pastiche or eclecticism, but they had a challenge to meet, a possible source of inspiration such as Velasquez was for Manet, or Saint-Simon for Proust. p. 38

Jean-Paul Clébert, Paris insolite (Denoël, 1952) p. 44

The great Samaritaine store…climbed by King Kong in a famous advertisement of the 1970s. p. 63

…Touche pas la femme blanche, an excellent parody Western shot inside the hole… p. 69 (dir: Ferreri (1974); the hole was for the Métro.)

Newton

“gigantic shopping machine” (Gruen), p. 15

…brand-new cars from local dealerships parked beneath the skylights in the main corridor…p. 28

In the cold quiet of winter, when all the money was spent and the hours of part-time employees cut, our visits became less frequent. Yet the waiting always seemed endless, like my mother might never materialize at that door. Like the mall might never give her back. p. 31

A certain sense of mystery surrounded each employee that exited the mall…It was fascinating to watch the transition, like actors unwinding backstage after a performance. But it also offered a candid look at the divide between between employees and customers. p. 33

“Main Street in a space ship.” (William Severini Kowinski) p. 45

…a cluster of coin-operated rides in an atrium or end court. p. 118

“There are no unsacred places; there are only sacred places and desecrated places.” (Wendell Berry) p. 119

The fictive shoppers in these renderings, more formally referred to as ”people textures” and “populating images” in the vernacular of architects, are intended to give a sense of scale. For that reason, some architects even call them “scalies.” pp. 136-7

“You can take the most random rendering and just stick in a few people…Suddenly it’s meant to make the entire building beyond critique; it’s already part of our city.” (Geoff Manaugh) p. 137